Stockman’s account shows how payments aided leprosy treatment

Jack Gibbs spent years in leprosy facilities. His story reveals how receiving Invalid Pension meant he could spend time recovering instead of working.

He said, ‘You’d better come back to East Arm [Leprosarium] Jack and get on the pension.’ I hadn’t been getting the pension … After the operation there I could get about a bit better.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| gibbs-son-of-jimmy-excerpts.pdf | 4.4 MB |

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| son-of-jimmy-excerpts .docx | 87.99 KB |

Between the 1930s and 1980s, the government sent Aboriginal people with leprosy to quarantine in leprosy facilities. Until the 1960s, Aboriginal people couldn’t get government payments if they lived on a settlement, reserve or station. The government considered patients in leprosy facilities to be ineligible too.

Gibbs’s early diagnosis

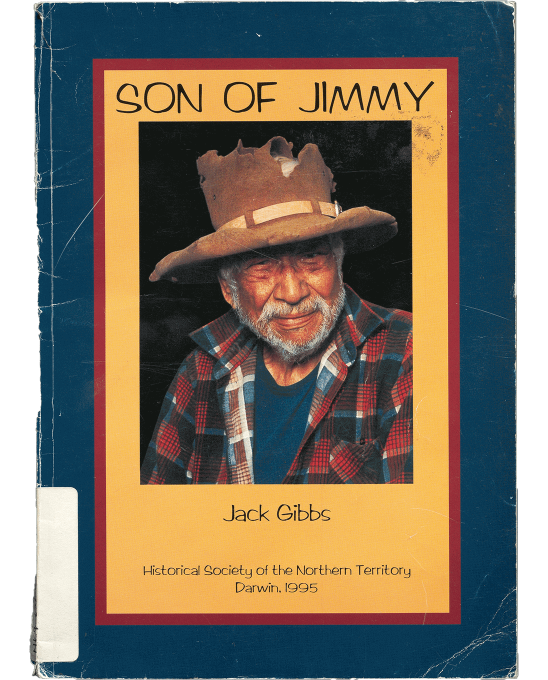

Mara / Marra man, Jack Gibbs, talks about his time as a leprosy patient in his autobiography, Son of Jimmy. These are 2 excerpts from his book.

In the first excerpt, Gibbs talks about having foot pain and a doctor diagnosing him with leprosy in 1948. The doctor sent him to the Channel Island Leprosarium in the Northern Territory for treatment and to quarantine.

In 1954 Gibbs moved to the newly opened East Arm Leprosarium, also in the Northern Territory. He then spent some time out of the facility, working in different jobs.

During this time, Gibbs’s partner Nancy Croft had been getting a small pension. However, Gibbs wasn’t able to get any financial help.

Receiving pension at East Arm

In the 1960s, patients in leprosy facilities became eligible for government payments. Gibbs’s doctor, Dr JC Hargrave, suggested Gibbs return to East Arm for treatment and to apply for Invalid Pension.

The second excerpt describes Dr Hargrave’s visit to East Arm. Gibbs also gives insight into the daily lives of patients at the leprosarium, including treatment and surgery. He has positive memories of his time in the facility.

Getting Invalid Pension allowed Gibbs time to recover from treatment without continuing physically demanding work that would worsen his condition.

Although patients became eligible for payments in the 1960s, government officials didn’t agree on how to pay them. Gibbs didn’t comment on whether the government paid him directly, however, other accounts show that the government often paid facility managers instead of patients.

Not long after Gibbs left East Arm, his pension stopped getting paid. Gibbs had to ask for help again from friends and Dr Hargrave in order to regain access to his pension.

Gibbs and Croft returned to East Arm many times over the years, usually for Gibbs to receive treatment. The couple were there when the settlement closed in 1982 (Robson 2012:250).

Gibbs recorded his life story on cassette tapes in the early 1990s. Gibbs was helped by others to transcribe these recordings into text and then edit and publish his book.

Permissions

Uncle Jack Gibbs’s family members Uncle Ricky Petterson and families and Aunty Yvonne Nona and families have provided permission for the inclusion of these excerpts.

Permissions were also provided by the Historical Society of the Northern Territory.

Citation

Gibbs J (1995) Son of Jimmy, Historical Society of the Northern Territory, Darwin.