Oral history reveals difficulties seeking financial security

Even when government help was available, it was often not enough to help disadvantaged Aboriginal families out of poverty. One man’s oral history shows years of upheaval trying to find security for his family.

I was on Social Service and couldn’t get work … We walked away from it all with nothing ...

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| nicholls-oral-history-excerpt.pdf | 1.77 MB |

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| nicholls-oral-history-excerpt-plaintext_0.docx | 285.19 KB |

Many Aboriginal families struggling financially had to move away from Country, whether by force or to find work and opportunities. Help from government often didn’t lead to families getting out of long-term and historic poverty.

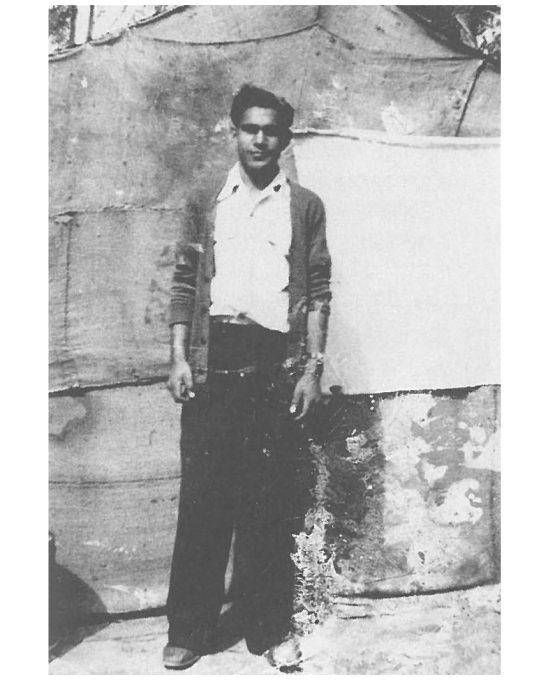

This excerpt from an oral history recorded with Yorta Yorta man Bevan Nicholls is a first-hand accounts of this experience. His story was published in a large collection of oral histories with Koori people recorded by Alick Jackomos and Derek Fowell in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Challenges in early life

Nicholls was the son of Gladys Nicholls and Herbert Nicholls, both of Cummeragunja Reserve on Yorta Yorta Country along the Murray River.

Nicholls talked about the difficulties his family and community endured following the historic walk-off from Cummeragunja Reserve in 1939. Families left their land in protest of the poor conditions forced on them by reserve management. Following the walk-off, food was scarce and finding ongoing work and a stable place to live was hard. Nicholls talked about the ongoing fear families had of the Aborigines Protection Board taking away their children.

Nicholls endured other struggles as a child, including the loss of his father and the need to start working as a farm labourer from 14 years old.

Seeking financial security

A key theme Nicholls talked about was his ongoing difficulties in being able to become financially secure. ‘It seems as though you move around in a circle with the same old story,’ he said.

Nicholls recalled his experience getting a government loan for a farm in Piangil near the Murray River. While he and his sons worked hard to establish the land, after a mouse plague and drop in wool prices, they were unable to make the loan repayments.

Made to move off the farm, Nicholls was ‘on social service and couldn’t get work … we walked away from it all with nothing’.

Moving away from the area was difficult for Nicholls and his family due to their connection to land. ‘The river bank is always there for us when we are in trouble,’ he said.

As well as this Nicholls explained that to live ‘in town’ with white people trapped them in poverty. In his experience, this was barely different from mission days ‘when you waited for the ration hand-out’.

Nicholls again felt let down a few years after losing the farm by lack of financial support when he needed it most. He had the opportunity to purchase a house for a discounted rate and thought he might be able to get help from the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, but could not.

The Nicholls family moved once again to Cummeragunja, ‘right back to where we started’.

Nicholls’s experiences show the ongoing struggle many Aboriginal families faced trying to survive financially in a system designed to not include them. Seeking security often meant a difficult choice between maintaining connection to Country, or moving to find work while facing exclusion from white communities.

Many important Aboriginal activists and leaders who emerged in the 1930s and 1940s came from Cummeragunja, including Pastor Doug Nicholls, Gladys Nicholls, William Cooper, Jack Patten, Thomas Shadrach James and family, Margaret Tucker and Geraldine Briggs.

Jack Patten was editor of the first Aboriginal-led publication, which publicised and advocated for Aboriginal rights. Shadrach Livingstone James was an activist who fought for citizenship rights in many ways, including by writing to the prime minister in 1945.

Yorta Yorta woman Merle Jackomos was a child when her family stayed on during the Cummeragunja walk-off. Later in life, Merle married Alick Jackomos, who was the co-editor of this book. The couple both devoted their lives to advocacy for Aboriginal rights.

The production of this oral history collection was guided by the Victorian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Advisory Committee.

Permissions

Permission to reproduce this excerpt was granted by the daughters of Bevan Nicholls and Lettie Nicholls, Jan Muir (Nicholls) and Glenda Nicholls.

Permission was granted by the daughter of Merle Jackomos OAM and co-editor Alick Jackomos, Esmai Manahan.

Permission from co-editor Derek Fowell was facilitated through family members.

Permission was also granted from the copyright holder, Museums Victoria.

Citation

Nicholls B (1991) ‘Bevan Nicholls: we had moved around in a circle, right back to where we started’, pp 106–109, in Jackomos A and Fowell D (eds) Living Aboriginal history of Victoria: stories in the oral tradition, Museum of Victoria, Craftsman Press, Melbourne.