Memoir shows wide-ranging discrimination

Doreen Kartinyeri’s life story holds details of a number of issues that her family faced in accessing government payments, including issues with living on missions, exemptions and child removal.

… sisters and brothers often received different benefits … same mother and father; same features, but different entitlements because one was lighter skinned than the other.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| my-ngarrindjeri-calling.pdf | 3.22 MB |

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| my-ngarrindjeri-calling-plaintext_1.docx | 53.63 KB |

Aboriginal people faced discrimination on many fronts when getting government payments. This source includes excerpts from the life story of Ngarrindjeri historian Doreen Kartinyeri. Her account includes experiences that were common for many Aboriginal people.

Eligibility based on skin colour

Kartinyeri explained the complicated way that social services payments were distributed by South Australian authorities.

Kartinyeri recalls that her mother got Child Endowment to help take care of her, but that other Aboriginal mothers didn’t. She writes that it depended on the colour of their skin:

… sisters and brothers often received different benefits … Aunty Opie and her sister Aunty Joycey (nee Wanganeen) when they started to have children, one was entitled to child endowment and the other wasn’t. Same mother and father; same features, but different entitlements because one was lighter skinned than the other.

Kartinyeri writes about her relatives lobbying the government in the 1950s. Percy Rigney and Bob Wanganeen went to Canberra to ask for ‘full blood’ women to get Maternity Allowance and Child Endowment.

Issues with documents

Kartinyeri tells of how the state Aboriginal Protection Board took her newborn sister, Doris, to Colebrook Home. Kartinyeri’s mother, Thelma, had died in childbirth in 1945.

Kartinyeri’s father, Oscar, was given paperwork by government officials about Doris. He couldn’t read and thought that he was signing to get Child Endowment. However, the paperwork actually made Doris a ward of the state and she was removed from the family.

These events had a devastating impact on Kartinyeri’s family. Soon after this, Kartinyeri was sent away to the Salvation Army Home in Fullarton, near Adelaide.

Indirect payments

Although Kartinyeri’s grandmother was entitled to get Child Endowment to help care for Kartinyeri’s younger brother and sister, they didn’t see the payment.

As was common at the time, the Point Macleay Mission authorities collected the payments on behalf of residents and decided how to spend the money.

Exemptions and living on missions

In her memoir, Kartinyeri explained the process of exemption. If the South Australian Government considered an Aboriginal person exempt from state protection laws they could get a pension. However, they had to deny their Aboriginality and move away from their communities and off their land.

One of the many impacts this had was the separation of families. When Kartinyeri’s grandmother fell ill in 1950, not all family members could go to help. However, Kartinyeri was able to return to Point Macleay Mission, now called Raukkan, in South Australia where her grandmother lived and where Kartinyeri had grown up.

Her grandparents relied on Kartinyeri’s income as they were only able to get rations. They weren’t eligible for Old-age Pension because of their Aboriginality. As well as working as a domestic for the mission superintendent, Kartinyeri sold feather flowers, mats, and baskets to help make money.

South Australia’s exemption policies ended in 1962.

Kartinyeri’s stories contain detail about the difficulties Aboriginal people faced getting government payments. They show the real-life impacts of the government’s discriminatory policies and the advocacy required to create change.

Doreen Kartinyeri’s autobiography was written with the assistance of Sue Anderson. These excerpts were provided by AIATSIS, which holds copies of the book.

Permissions

Permissions to include this excerpt were granted by Doreen Kartinyeri’s son Klynton Wanganeen and by Dr Sue Anderson.

Citation

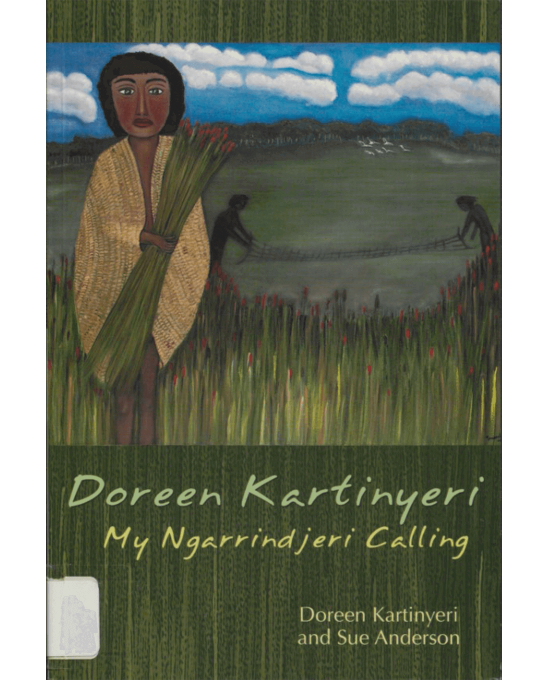

Kartinyeri D and Anderson S (2008) My Ngarrindjeri calling, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.