People face challenges proving age without a certificate

For a long time, Aboriginal people weren’t given birth certificates. Walaru’s experience is an example of how difficult it was to prove age and show eligibility for Old-age Pension.

Please will you help me to apply for an Old Age Pension ... I am not up to work now ... I believe I am seventy.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| walaru-norman-bilson-photo.pdf | 880.54 KB |

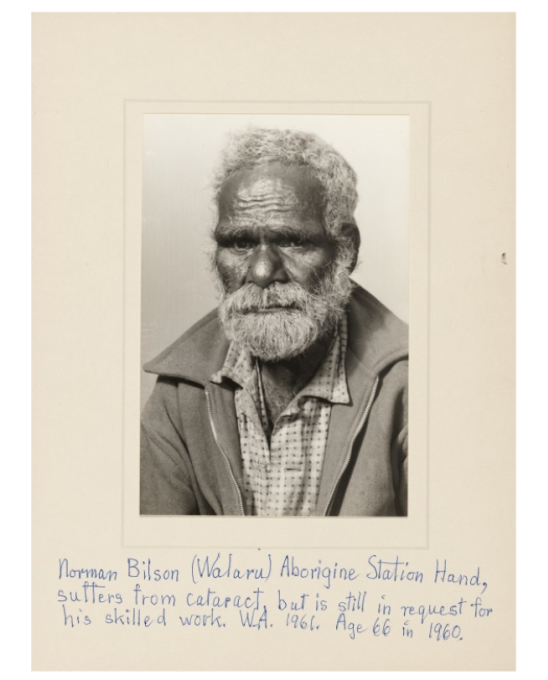

This portrait of Norman Bilson, or Walaru, was taken in 1961 to support his claim for Old-age Pension. Walaru was a Nanatadjarra man who worked as a stockman in the Goldfields area of Western Australia all his life.

In 1959, changes to the Social Services Act meant that he was eligible for Old-age Pension. However, it wasn’t simple for him to apply.

Walaru’s claim

Walaru applied for Old-age Pension in a letter to the Kalgoorlie District Native Welfare Officer. These state officers made decisions about government payments. He dictated these words:

Please will you help me to apply for an Old Age Pension to be paid to me in money at the Post Office in Kalgoorlie. I feel I am finished now and my eyesight is going. I can't do any more station work ... I have always worked on the same station ... But I am not up to the work now. My age is seventy. I believe I am seventy because I was a man when the First War started.

The District Officer replied that ‘Norman Bilson is not seventy years of age ... and is not yet old enough for the Age Pension’.

Walaru was born at a time when the government often didn’t create birth certificates for Aboriginal people. Reasons included that they were born remotely or that they were removed from their families at birth. Proving his age was a difficult task without official documents.

Help to prove age

Walaru had ongoing contact with Mary Bennett, a settler woman who fought for Aboriginal rights. Bennett had tried to get government support for Walaru and his family for some time.

Bennett helped Walaru gather more proof of his age. She wrote up a detailed story of Walaru’s life and gathered letters from people who had known Walaru for a long time. She also took Walaru to a doctor who found he had cataracts. She arranged for this photo to be taken to support Walaru’s claim.

After looking into Walaru’s claim, the government decided he was eligible for Invalid Pension instead of Old-age Pension because of his cataracts. It took over a year for the government to make this decision.

Advocacy for change

Bennett used photos like this to advocate for Aboriginal rights, including for government payments. Some activists at the time used photos as evidence of awful living conditions that Aboriginal people faced to fight for improvements (Lydon 2012:175). Bennett, however, chose to show the strengths and individuality of Aboriginal people in her work. She outlined the specific injustices they faced, while showing them as confident.

Settler activists, such as Shirley Andrews from the Council for Aboriginal Rights in Victoria, used the photos to support individual cases for government payments and also to build momentum for citizenship rights for Aboriginal people.

Experiences like Walaru’s were described in the Yinjillli leaflet which Andrews co-authored in 1963. This tried to explain to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people how to access social security payments.

Maisie Harkin, member of the Bilson family, shared information about Walaru’s life. He was born in the Great Victoria Desert in Western Australia. As a young teenager, known as Norman Bilson, he worked as a drover at Mt Weld station. He would have been given tea, flour, sugar and tobacco in place of wages, at a time where there was no help from social services. Bilson followed the station owner to another station at Kookynie, working droving cattle until he was too old. He moved to Kalgoorlie, where his brother and other family members also lived.

Mary Bennett commissioned portrait photographs of Nanatadjarra and Wongi people living in Kalgoorlie, including this image of Walaru. These photographs and accompanying letters were sent to Shirley Andrews, secretary of the Council for Aboriginal Rights.

Bennett wrote to Andrews about the difficulties Aboriginal people in Kalgoorlie faced in getting access to social services. Accounts based on Bennett’s letters were included in the newsletter Smoke Signals, which was published by the Aborigines Advancement League of Victoria. The quote from Walaru comes from the article ‘The way is hard’, published in Smoke Signals in April 1960.

In 2007, copies of the photographs that Bennett commissioned were returned to Bilson family members in Kalgoorlie by Dr Sue Taffe.

Access more information about these photographs on the Civil rights documents page of the Collaborating for Indigenous rights 1957–1973 website written by Dr Taffe and hosted by the National Museum of Australia.

This copy of the photograph is sourced from the collections of the State Library of Western Australia.

Permissions

Permission to include Waluru’s photograph and story here was granted by Walaru's great grandchild Amanda Bilson and Bilson family members, including Maisie Harkin.

Citation

Aborigines Advancement League of Victoria (April 1960) ‘The way is hard’, Smoke Signals,

1(1):25–33.

Maxine Studios (1961) Norman Bilson (Walaru) [black and white photoprint on mount], BA2641/17 in Mary Montgomerie Bennett and Ada Bromham collection of photographs, State Library of Western Australia, accessed 15 May 2023.